When investing, your capital is at risk and you may get back less than invested. Past performance doesn’t guarantee future results.

The role of inflation in the UK

Inflation is an important economic metric to judge the quality of life for UK residents. Inflation in the UK and EU/global inflation and related topics such as deflation and monetary policy play a part in British economic prosperity.

Big ideas

- A small level of inflation is healthy and necessary for the market. A healthy inflation rate is often regarded as about 2% yearly.

- Inflation adversely affects those who are on the bottom end of the socioeconomic ladder without assets.

- Central banks will use higher interest rates to keep inflation low. Free (0% interest) money will increase the cost of goods and services by flooding the market with excess liquidity.

QUOTE

“Inflation takes from the ignorant and gives to the well-informed.”

All serious investors and financial professionals understand inflation, as it can eat away at wealth if specific measures are not taken to use cash constructively.

Inflation can even be used to the advantage of those with bigger pockets. A rising cost of basic goods and services adversely affects poorer individuals, while many investors and traders make their fortunes during market downturns while others panic.

High inflation can be accurately characterised as penalising savers and those on a fixed income because the total monetary amount is weaker in purchasing terms. It is beneficial to those in debt and those who own assets such as real estate.

Inflation can even be used to the advantage of those with bigger pockets. A rising cost of basic goods and services adversely affects poorer individuals, while many investors and traders make their fortunes during market downturns while others panic.

High inflation can be accurately characterised as penalising savers and those on a fixed income because the total monetary amount is weaker in purchasing terms. It is beneficial to those in debt and those who own assets such as real estate.

What inflation is all about?

Inflation is simply a rise in the price of goods, also described as a decline in the purchasing power of money. Inflation rises yearly, so the same dollar or pound amount (such as $100) will purchase far less today than in 1980.

This is why inflation harms savers - there is no point in saving money when it will all be eaten by inflation. Inflation forces people to spend money instead and thus contributes to growth. Money has to be “set to work”, or it will become devalued with time.

Inflation can be classified into three types - cost-push inflation, demand-pull inflation, and built-in inflation.

Inflation in the UK is measured by calculating the cost of many goods and services over time to see the price difference. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the most commonly used goods index. Other indexes include the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) as well as the Wholesale Price Index (WPI).

This is why inflation harms savers - there is no point in saving money when it will all be eaten by inflation. Inflation forces people to spend money instead and thus contributes to growth. Money has to be “set to work”, or it will become devalued with time.

Inflation can be classified into three types - cost-push inflation, demand-pull inflation, and built-in inflation.

Inflation in the UK is measured by calculating the cost of many goods and services over time to see the price difference. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the most commonly used goods index. Other indexes include the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) as well as the Wholesale Price Index (WPI).

INFLATION: Lossers vs Winners

Losers:

📉 Savers

📉 Retirees living on fixed incomes

📉 Workers on a fixed income

📉 Borrowers on variable rates

📉 Whole economy - from general economic uncertainty

📉 Exporters less competitive

Winners:

📈 Debtors

📈 Governments with high public sector debt

📈 Owners of land and physical assets

📈 Firms that can cut real wages

📉 Savers

📉 Retirees living on fixed incomes

📉 Workers on a fixed income

📉 Borrowers on variable rates

📉 Whole economy - from general economic uncertainty

📉 Exporters less competitive

Winners:

📈 Debtors

📈 Governments with high public sector debt

📈 Owners of land and physical assets

📈 Firms that can cut real wages

Of course, inflation can also benefit people. People that own commodities such as precious metals, oil, or agriculture will benefit, as will property owners. Those with large debt also get a huge haircut in times of inflation because wages and income can go up to match inflation, but the amount owed is often at a fixed rate.

The rate of inflation is closely linked to the cost of money set through interest rates. A central bank (such as the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve, or the European Central Bank) adjusts the rate of borrowing money. A low-interest rate will result in a liquid economy with easier access to credit, which will eventually increase inflation.

The rate of inflation is closely linked to the cost of money set through interest rates. A central bank (such as the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve, or the European Central Bank) adjusts the rate of borrowing money. A low-interest rate will result in a liquid economy with easier access to credit, which will eventually increase inflation.

The three types of inflation

The three main types of inflation are:

- Demand-pull inflation - this occurs when there is an increase in demand for goods and services, but the supply of those goods and services cannot keep up with the demand. This results in an increase in prices.

- Cost-push inflation - this occurs when the cost of production increases, which in turn leads to an increase in the price of goods and services. For instance, if the cost of raw materials or wages increases, businesses may raise prices to maintain their profit margins.

- Built-in inflation - this occurs when inflation becomes embedded in the economy people come to expect it. For example, if workers expect a certain level of inflation when negotiating their wages, they may demand higher wages to compensate for expected inflation. This can lead to a self-perpetuating cycle of inflation, as higher wages lead to higher costs for businesses, which in turn leads to higher prices for goods and services.

Inflation can be specific to a sector or industry as opposed to the wider economy. The cost of cars might increase while the cost of computer manufacturing might decrease. However, everything in the economy is linked. So a rise in a given commodity or input product will increase all industries that rely on that product. Oil is a typical example.

When inflation becomes pronounced, it can lead to hyperinflation, which signifies a total collapse of the monetary economy. Money essentially becomes worthless. However, this is exceedingly rare.

When inflation becomes pronounced, it can lead to hyperinflation, which signifies a total collapse of the monetary economy. Money essentially becomes worthless. However, this is exceedingly rare.

Inflation forecast UK

It can be difficult to give an accurate UK inflation rate because it is a figure that is subject to multiple conditions. Economists and policymakers will always claim to have kept inflation to manageable levels or that it is at a manageable level, but this only works to a point.

At the time of this writing, inflation rates in the UK are huge. This is due to macroeconomic trends. The Covid-19 pandemic caused supply chain disruptions and geo-restrictions that invariably increased the cost of multiple products, aside from the direct economic fallout of closed borders and shuttered businesses.

UK interest rates are currently set at 4%, which is quite high. A high-interest rate hurts those looking for a loan, such as first-time mortgages and startup businesses. So a high rate can also send an economy into a recession as people struggle to pay the bills. It often takes 18 to 24 months for interest rates to have an effect on the economy and for reports to reflect this.

At the time of this writing, inflation rates in the UK are huge. This is due to macroeconomic trends. The Covid-19 pandemic caused supply chain disruptions and geo-restrictions that invariably increased the cost of multiple products, aside from the direct economic fallout of closed borders and shuttered businesses.

UK interest rates are currently set at 4%, which is quite high. A high-interest rate hurts those looking for a loan, such as first-time mortgages and startup businesses. So a high rate can also send an economy into a recession as people struggle to pay the bills. It often takes 18 to 24 months for interest rates to have an effect on the economy and for reports to reflect this.

QUOTE

“By a continuing process of inflation, the government can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens.”

The Bank of England wants inflation to return to 2% and has been raising rates for over 2 years now. It’s very important to keep inflation stable, but you can only raise interest rates for so long before it results in equal hardship. Inflation in the UK is at 10.4% in the 12 months up to March 2023. This is extremely high, and there is a known “cost of living crisis” in the UK, as measured by the CPI index of goods and services.

Consumer prices index and BoE forecasts

Source: BOE / ONS

Source: BOE / ONSPreviously, the Bank of England had predicted a fall in inflation to 2% by the end of 2023 in its August 2021 Monetary Policy Report. The rise in UK inflation is mainly due to increases in hotels, transport, restaurants, and energy prices. Inflation is often not spread out evenly across goods and services.

Inflation in Europe

Inflation figures are similar in Europe and the USA as compared to the UK. Inflation in the USA in the 12 months leading to January 2023 stands at 6.8%, as measured by the CPI. This is an extremely high figure. But it’s superior to the inflation profile of EU countries, which has an average of 10% inflation in January 2023, as measured by the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) across its 27 member states.

However, the highest inflation in Europe, as per Statistica, is due to countries such as Hungary (26%), Latvia (21%), Czechia (19%), and Estonia (18%). Developed countries are witnessing lower figures, such as Sweden (9%), Germany (9%), France (7%), Finland (7%), and Luxembourg (6%).

However, the highest inflation in Europe, as per Statistica, is due to countries such as Hungary (26%), Latvia (21%), Czechia (19%), and Estonia (18%). Developed countries are witnessing lower figures, such as Sweden (9%), Germany (9%), France (7%), Finland (7%), and Luxembourg (6%).

Harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP) inflation rate in Europe in March 2023, by country

Source: Statistica

Source: StatisticaAs can be observed from the level of inflation in the European Union, the situation is not optimal. The country with the lowest inflation (Switzerland, as of March 2023) is still above the 2% desired level, while the average inflation rate stands at 10%, five times higher than the acceptable range.

The rate of inflation also demonstrates that no country is immune to an increasingly globalised and interconnected world economy. The EU, US, and UK inflation rates are all far higher than the recommended 2% to 3%. More affordable countries are also seeing vastly increased inflation. As people immigrate from richer countries, they tend to gravitate towards affordable areas, pushing prices higher.

The rate of inflation also demonstrates that no country is immune to an increasingly globalised and interconnected world economy. The EU, US, and UK inflation rates are all far higher than the recommended 2% to 3%. More affordable countries are also seeing vastly increased inflation. As people immigrate from richer countries, they tend to gravitate towards affordable areas, pushing prices higher.

Inflation vs deflation: Opposite directions

Deflation is the opposite of inflation. With deflation, the cost of goods and services is going down. This means that the same amount of currency will buy more goods and services. So a certain amount of deflation is particularly good for the working class and those with decreased income potential, because they can more easily afford basic goods and services.

But too much deflation means an economy that does not produce anything or grow in a real sense. The weakest world economies are those where the cost of goods and services is ultra-low, such as Africa, South America, and the Middle East. There is little incentive to work or produce in such economies because they do not have functional governments or amenities to facilitate growth and productivity.

Deflation could also be termed negative inflation, such as -1% inflation. It occurs either because there are too many goods/services available or not enough money in circulation. Deflation can create a negative spiral because companies and families hoard money, and credit agencies tighten up on liquidity. Individuals and companies are more reluctant to spend money, which causes a deflationary spiral.

The lost decade of Japan is an example where a deflationary crisis hurt the economy. The reality of inflation vs deflation is quite simple. Central banks target inflation rates between 2 - 3% because this is an optimal range for the economy. However, due to the current rate of inflation in recent years, a deflationary period could be advantageous.

Deflation could also be termed negative inflation, such as -1% inflation. It occurs either because there are too many goods/services available or not enough money in circulation. Deflation can create a negative spiral because companies and families hoard money, and credit agencies tighten up on liquidity. Individuals and companies are more reluctant to spend money, which causes a deflationary spiral.

The lost decade of Japan is an example where a deflationary crisis hurt the economy. The reality of inflation vs deflation is quite simple. Central banks target inflation rates between 2 - 3% because this is an optimal range for the economy. However, due to the current rate of inflation in recent years, a deflationary period could be advantageous.

Why do governments not want deflation?

Governments generally do not want deflation because it can have negative impacts on the economy, such as:

- Debt burden - deflation can increase the real value of debt, making it more difficult for individuals, businesses, and governments to pay back their loans. This can lead to defaults and bankruptcies, which can have ripple effects on the economy.

- Reduced spending - deflation can also lead to a reduction in spending, as consumers and businesses delay their purchases in anticipation of further price decreases. This can lead to a decrease in demand for goods and services, which can result in lower production, profits, and employment.

- Lower economic growth - deflation can also reduce economic growth, as businesses may delay investment in new projects and expansions due to lower demand and profitability.

- Increased real interest rates - deflation can lead to an increase in real interest rates, which can make borrowing more expensive and decrease investment.

To avoid the negative impacts of deflation, governments often use monetary and fiscal policies to maintain price stability and promote economic growth. For example, central banks may use tools such as lowering interest rates, increasing the money supply, and quantitative easing to prevent deflation and stimulate economic activity. Similarly, fiscal policies such as government spending and taxation can also be used to stimulate economic activity during periods of deflation.

Inflation rates UK, USA, and the globe

The rate of inflation across the world is indicative of systemic crises. What is important to understand is that the effects of policies usually take between 1 to 2 years to affect the economy in a major way. We are most likely witnessing the effects of a prolonged Covid-19 pandemic with its associated health risks and costs, as well as its economic shutdowns and widespread government spending.

The pandemic had a major effect on small business owners. This can be coupled with the fact that 40% of all existing US dollars (the world’s reserve currency) were printed in 2021 in order to deal with the crises. The Ukraine war also sparked a notable increase in the cost of goods and services, particularly energy prices and commodities such as wheat.

It’s also worth mentioning that not all economists, politicians, and policymakers are in favour of inflation. Ronald Regan and Margaret Thatcher, right-wing conservatives, were very critical of inflation as a tax that robbed people. Economists such as John Maynard Keynes viewed inflation as wealth confiscation, while Milton Freedman stated it to be a form of tax without any legislation.

The pandemic had a major effect on small business owners. This can be coupled with the fact that 40% of all existing US dollars (the world’s reserve currency) were printed in 2021 in order to deal with the crises. The Ukraine war also sparked a notable increase in the cost of goods and services, particularly energy prices and commodities such as wheat.

It’s also worth mentioning that not all economists, politicians, and policymakers are in favour of inflation. Ronald Regan and Margaret Thatcher, right-wing conservatives, were very critical of inflation as a tax that robbed people. Economists such as John Maynard Keynes viewed inflation as wealth confiscation, while Milton Freedman stated it to be a form of tax without any legislation.

How to deal with inflation in the UK

While a healthy 2% inflation rate is beneficial to the economy, the current 6% - 10% annual average for developed countries is not sustainable and can be said to function as a form of tax that adversely affects those on limited incomes.

After all, the inflation rate in the UK has led to a cost of living crisis. Accommodation in urban centres is sky-high and many are finding it difficult to afford basic services. This is a direct result of government and central bank policy.

However, you can invest in stocks and other securities that perform well during inflation. This includes stocks related to commodities and real estate, which are hedges against inflation.

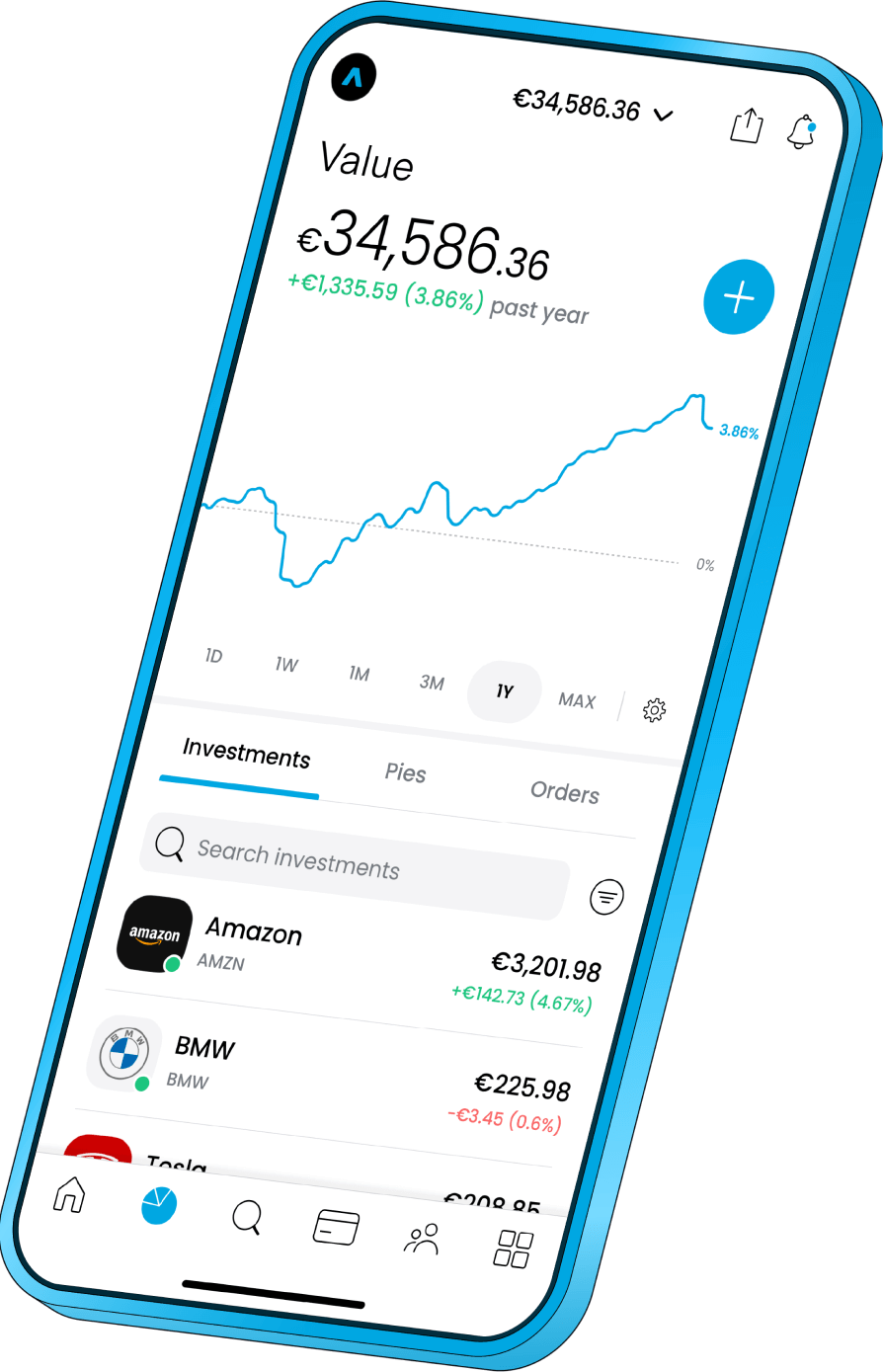

Trading 212 offers zero commission trading for UK residents as well as fractional shares to diversify your portfolio. Inflation-resistant stocks are a great way to protect yourself against inflation in the UK.

After all, the inflation rate in the UK has led to a cost of living crisis. Accommodation in urban centres is sky-high and many are finding it difficult to afford basic services. This is a direct result of government and central bank policy.

However, you can invest in stocks and other securities that perform well during inflation. This includes stocks related to commodities and real estate, which are hedges against inflation.

Trading 212 offers zero commission trading for UK residents as well as fractional shares to diversify your portfolio. Inflation-resistant stocks are a great way to protect yourself against inflation in the UK.

Recap

The general consensus is that a low inflation rate between 2% - 3% is optimal for the economy. If inflation is too high, it will have a negative impact, particularly for low-income households. However, inflation rates are currently much higher than they should be in the UK, Europe, and the US.

While deflation is often a negative sign for the economy, given how high inflation has been in the past 5 years, a lowering of the cost of goods and services might be welcome. At least, the rate of inflation in the UK and abroad needs to come down to a safer range.

While deflation is often a negative sign for the economy, given how high inflation has been in the past 5 years, a lowering of the cost of goods and services might be welcome. At least, the rate of inflation in the UK and abroad needs to come down to a safer range.

FAQ

Q: Why do economists hate deflation?

It is generally accepted that economies are meant to grow. So a small amount of inflation is healthy each year because it is a sign that the economy is growing. So economists are quite critical of an economy that is going “backwards”. Yet there are more tangible reasons to fear deflation as opposed to inflation.

Deflation can result in an economic death spiral because companies make fewer profits, which leads to unemployment, which leads to less government revenue and, thus more deflation. Deflation also makes paying back debt extremely hard, resulting in lots of defaults and the associated economic fallout. Most assets of reasonable size have a loan against them (property, land, cars, businesses, etc.).

Deflation can result in an economic death spiral because companies make fewer profits, which leads to unemployment, which leads to less government revenue and, thus more deflation. Deflation also makes paying back debt extremely hard, resulting in lots of defaults and the associated economic fallout. Most assets of reasonable size have a loan against them (property, land, cars, businesses, etc.).

Q: Who benefits the most from deflation?

In the long run, nobody really benefits from prolonged deflation. For commodity owners and manufacturers, the cost of production can be more than what you get from the final product. While the price of goods and services may have come down, nobody has any cash to spend anyway.

However, inflation and deflation are relative concepts. With the rate of inflation in the UK and across the globe, deflation is very much a good thing right now. The cost of living has gotten too high for most people to live a comfortable quality of life.

And in 2015, Switzerland introduced negative interest rates, which many economists believed would send the economy into a recession. The result was a prospering economy with low employment rates and a net increase in spending power.

However, inflation and deflation are relative concepts. With the rate of inflation in the UK and across the globe, deflation is very much a good thing right now. The cost of living has gotten too high for most people to live a comfortable quality of life.

And in 2015, Switzerland introduced negative interest rates, which many economists believed would send the economy into a recession. The result was a prospering economy with low employment rates and a net increase in spending power.

Q: What is the difference between deflation and disinflation?

Deflation refers to a negative rate of inflation. If the cost of consumer goods, such as the CPI, is going down on a yearly basis, this would be deflation. But disinflation merely refers to a reduction in the current rate of inflation. If the current inflation rate is 8% and went down to 6%, that would be a disinflation rate of 2%. Disinflation occurs far more commonly than deflation.

This is why disinflation is often beneficial, while deflation alarms economists far more. Stocks can do well in a disinflationary environment, and bonds can deliver higher returns as central banks will be more likely to reduce interest rates.

This is why disinflation is often beneficial, while deflation alarms economists far more. Stocks can do well in a disinflationary environment, and bonds can deliver higher returns as central banks will be more likely to reduce interest rates.